Mastering the Game of Go

Published:

Introduction

Hello everyone! In this blog post, I will summarize, highlight and explain the most important concepts and ideas of the papers “Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search” by Silver, David et al. (2016) and “Mastering the Game of Go without Human Knowledge” by Silver, David et al. (2017). The work of David Silver et al. marks a milestone in the field of artificial intelligence, as it presents the development of AlphaGo and AlphaGo Zero, two computer programs that have revolutionized the game of Go and demonstrated the power of deep learning and reinforcement learning in mastering complex tasks. I hope you enjoy reading this blog post, and find it informative and inspiring!

Why Go?

Go is an ancient board game that originated in China more than 3000 years ago. It is played by over 40 million people worldwide, and has been considered a pinnacle of human intelligence and creativity. The game is simple to learn, but extremely complex to master. The number of possible positions on the 19x19 board is estimated to be around $10^{170}$, which is more than the number of atoms in the observable universe. Considering Deep Blue’s victory over Garry Kasparov in 1997 in chess, Go was considered to be the next big challenge for artificial intelligence, as traditional search methods are not suitable for exploring such a vast search space.

A 1-vs-1 Game on a 19x19 Board

Feel free to skip this section if you are already familiar with the game of Go. For the rest of you, here is a brief introduction:

The game of Go is played by two players, Black and White, who take turns placing stones of their color on the intersections of a 19x19 grid. The objective of the game is to surround more territory than the opponent, as well as capture the opponent’s stones by depriving them of liberties. A liberty is an adjacent empty point on the board. A stone or a group of connected stones of the same color is captured and removed from the board when it has no more liberties. A player can pass instead of placing a stone, and the game ends when both players pass consecutively. The score is then calculated by counting the number of empty points enclosed by each player’s stones, plus the number of captured stones. The player with the higher score wins the game.

Go is characterized by perfect information, meaning both players have complete knowledge of the entire state of the game at all times. Every move made is visible and known to both Black and White, ensuring that there are no secrets or hidden information. Furthermore, there’s no draw in Go due to specific rules like superko or positional superko that prevent infinite repetitions and ensure a decisive outcome. Each game concludes with a clear winner and loser. For more details on the rules of go, you can refer to this Wikipedia article.

How to represent Go positions?

To train and evaluate AlphaGo, the algorithm needs a representation of the state of the go board in a way that is suitable for neural networks. The representation used by AlphaGo is based on a set of 17 feature maps, each of which is a 19 x 19 matrix of binary values. The first two feature maps indicate the presence of white and black stones on the board, respectively. A one entry indicates the presence of a stone, and a zero entry indicates the absence of a stone. The next 14 feature maps encode the history of the board by showing the positions of white and black stones for the last seven moves. This allows the algorithm to capture the temporal dynamics of the game and the effects of the ko rule. The last feature map indicates whose turn it is to play by having a value of 1 for all points if it is black’s turn, or 0 otherwise. In principle, one bit would be enough to represent the turn, but using a feature map is more convenient and has no downsides. The 17 feature maps are then stacked together to form a 17 x 19 x 19 input tensor for the neural networks. This representation is simple, yet effective, as it captures the essential information about the board state and the game rules.

Mapping Go to a Deep Learning Problem

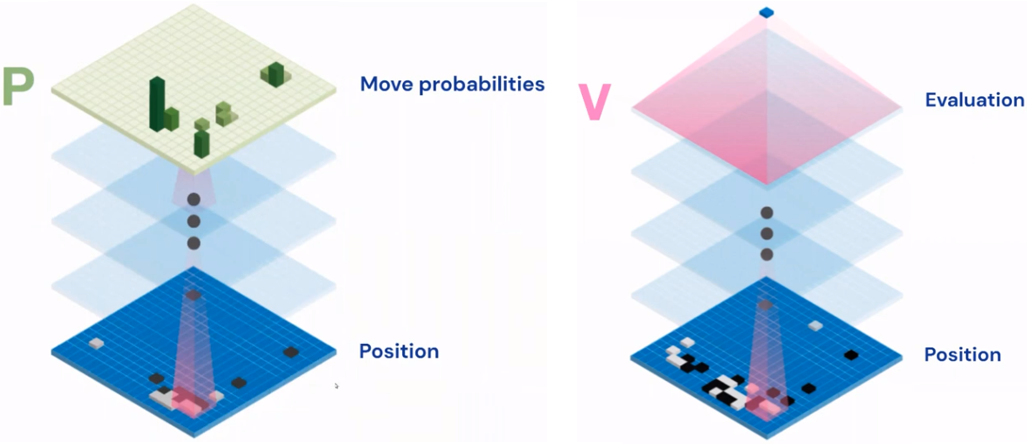

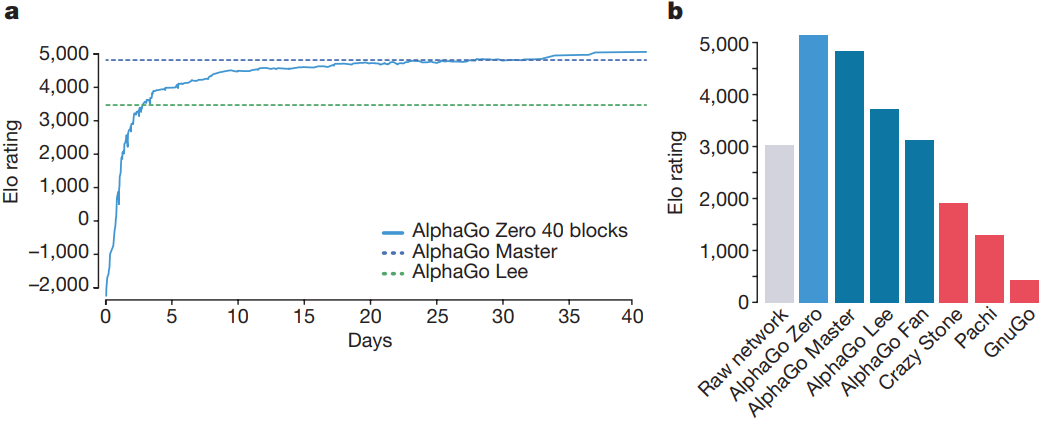

The heart of the AlphaGo alogorithm is a combination of two neural networks, a policy network and a value network. Now that we know how to represent the state of the go board, we can use this representation to train and evaluate these neural networks. Both networks are deep convolutional neural networks that take the current board position as input. The policy network outputs a probability distribution over all possible moves, suggesting which move to play, wheras the value network outputs a real-valued number between -1 and 1, which represents the predicted probability of winning the game from the current position.

The Training Procedure

The training of AlphaGo can be divided into three stages:

- Training the policy network (Supervised Learning)

- Improving the policy of the policy network (Reinforcement Learning)

- Training the value network (Supervised Learning)

First Stage

In the first stage, the policy network was trained on a large dataset of human expert moves, consisiting of 30 million positions, to mimic the human style of play. That means for a given board position, the policy network outputs a probability distribution over all possible moves, and the move that was actually played by the human expert is used as the target label. By calculating the cross-entropy loss between the predicted move probability distribution and the actual one, the policy network improves its ability to predict moves made by human experts. As a result, the policy provided by the network can predict human moves with high accuracy. Therefore, it is comparable in performance to human experts in the game of Go.

Second Stage

In the second stage, AlphaGo engaged in millions of self-play games. During this process, the policy was further refined through reinforcement learning (RL). This approach promoted moves that led to victories and suppressed moves that resulted in losses, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of the policy. Interestingly, the self-play games were not just between the current best policy iteration. They also involved a policy from a random previous iteration as an opponent. This approach was designed to prevent overfitting, ensuring that the current policy remained robust and generalized well to new situations. They want to ensure that the policy is not only good at playing against itself, but also against other policies.

Third Stage

Subsequently, the value network was trained using the outcomes of the self-play games as labels. This approach allowed the system to learn from its own gameplay experiences. The training process utilized the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function. This function measures the average squared differences between the network’s predictions and the actual outcomes. By minimizing this loss, the value network improved its ability to predict the probability of winning the game from any given position.

Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) in AlphaGo

Before we delve into the specifics of Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), it’s important to understand why simpler approaches fall short and how the use of two trained neural networks can offer significant advantages.

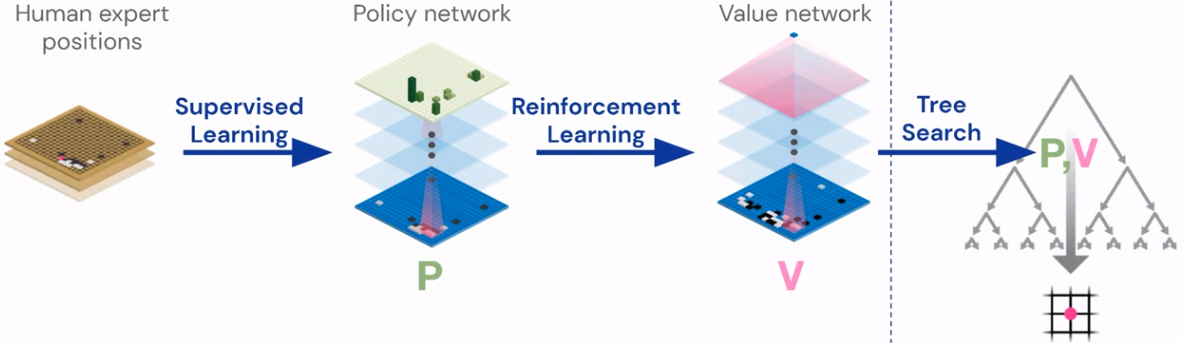

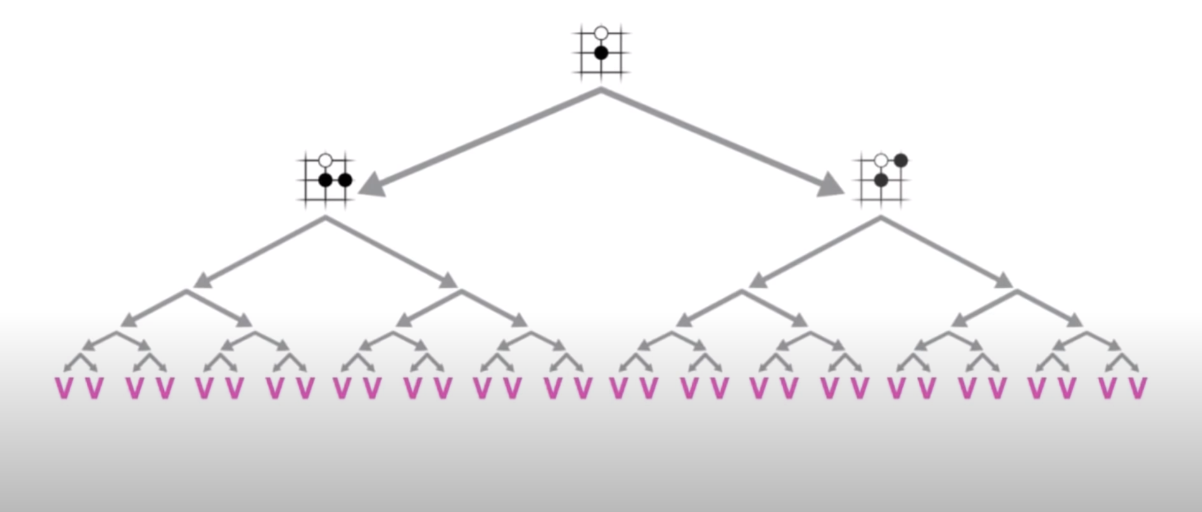

Exhaustive Search is not feasible

In theory, one could play a perfect game of Go by calculating all possible continuations from a given position and choosing the move that statistically leads to the highest number of wins. However, with an average of 150 possible moves per position and a typical game of Go lasting for 250 moves, an exhaustive search to find the best move is infeasible. It would require evaluating an astronomical number of positions, taking longer than the age of the universe even with the fastest computers available. Therefore, a more efficient approach is needed to find the best move in a reasonable amount of time. AlphaGo achieves this by using its two neural networks to reduce the search tree in two ways: by reducing the breadth and the depth.

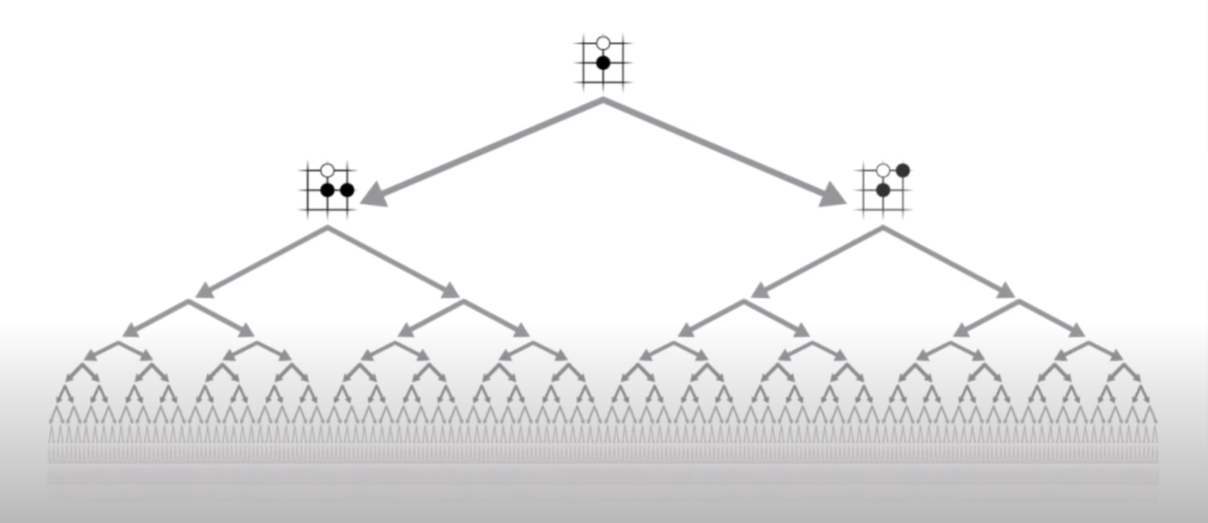

Reducing the Breadth with the Policy Network

The policy network predicts the probability distribution over all possible moves for a given board position. This network can be used to reduce the breadth of the search tree by focusing on the most promising moves. Instead of evaluating all possible moves, the search tree only considers the moves with the highest probability. This significantly reduces the number of nodes in the search tree, making the search more efficient.

Reducing the Depth with the Value Network

Determining whether a move is good or not might seem to require playing the game until the end to see who wins. However, if we had a perfect estimator that could predict the probability of winning with absolute certainty, we would only need to simulate one move deep into the future and pick the move for which the estimator predicts the highest probability of winning. While we don’t have a perfect estimator, the value network improves with more training. This network can be used as an estimator to reduce the depth of the search tree by estimating the value of the remaining moves without needing to simulate the game until the end. This further reduces the number of nodes in the search tree and makes the search more efficient.

Combination of MCTS with two Neural Networks

By integrating the two neural networks with Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), AlphaGo was able to concentrate on the most crucial parts of the search tree and explore them more systematically and deeply. This gave AlphaGo an advantage over its human opponents, who often fell prey to cognitive biases and errors, such as delusion (misjudging the position for 20-30 moves ahead) or overconfidence (underestimating the opponent’s strength).

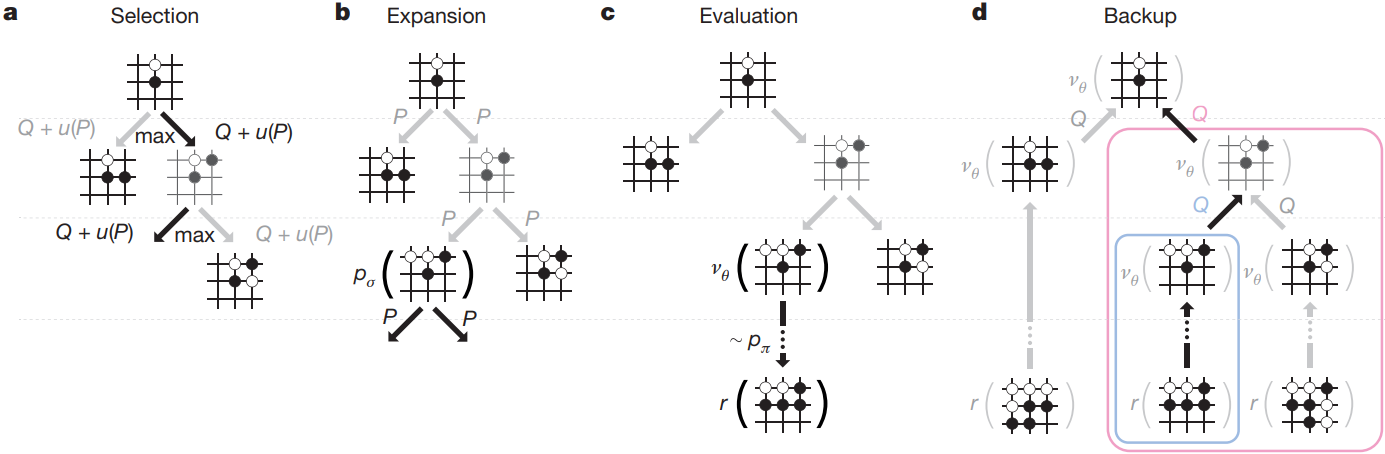

MCTS is a method that strikes a balance between exploration and exploitation by constructing a search tree that expands with each iteration. It consists of the following four steps:

- Selection: Starting from the root node, the tree is traversed by iteratively selecting the most promising child node. The selection is based on choosing the action that maximizes the metric $Q(s, a) + u(s, a) = \frac{W(s, a)}{N(s, a)} + c_{puct}P(s, a)\frac{\sqrt{\sum_{b} N(s, b)}}{1 + N(s, a)}$ until a leaf node is reached. Intuitively, the first term reflects if an action has been successful based on the previous simulations (exploitation). The second term reflects the prior probability of taking an action, as well as the number of visits to that node (exploration). By balancing these two terms, the algorithm can trade off between exploiting the best-known actions and exploring new actions that might lead to better outcomes.

- Expansion: The selected leaf node is expanded by adding the most probable child nodes to the tree, as determined by the probability output of the policy network.

- Evaluation: All expanded nodes are evaluated by simulating how the game might proceed until the end of the game is reached. For the simulation, moves are sampled according to the probability distribution provided by the policy network. The result of the simulation, in combination with the estimation provided by the value network, is then used to update the search tree.

- Backpropagation: The result of the evaluation is backpropagated up the search tree to update the statistics of the nodes visited during the selection phase. After this, the next iteration begins.

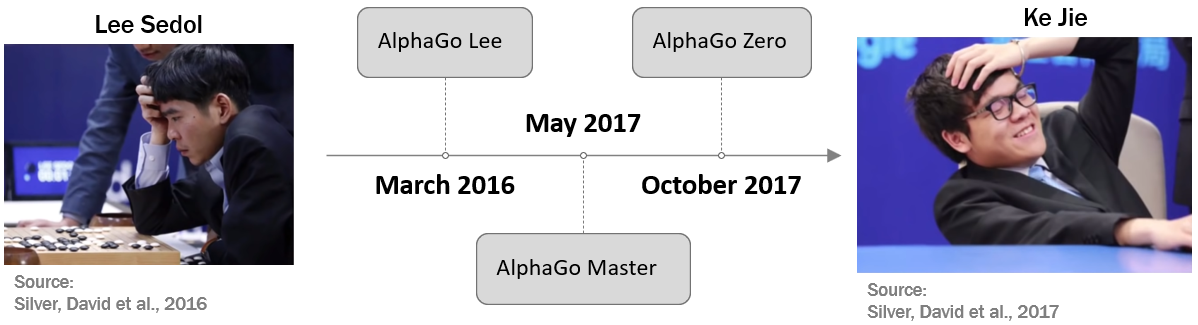

Performance of AlphaGo

In March 2016, the inevitable happened: AlphaGo was able to defeat Lee Sedol, one of the greatest Go players of the last decades and the winner of 18 world titles, by a score of 4-1 in a historic match in Seoul. This was the first time that a computer program won against a world champion in Go. The match was watched by millions of people around the world and was considered a milestone in the development of artificial intelligence.

In May 2017, AlphaGo Master, an successor AI developed by DeepMind, faced off against Ke Jie, who was then ranked as the world’s number one player. The match took place in China and ended with AlphaGo Master emerging victorious with a score of 3-0. But this wasn’t AlphaGo Master’s only achievement. It also played online against various Go masters and astonishingly won 60 out of 60 games. Further, it did not loose once to its predecessor version. This impressive performance can be attributed to the use of state-of-the-art deep residual networks instead of convolutional neural networks and even more iterations of RL during training.

After such an impressive performance, one might assume that there was little room for further improvement. However, the DeepMind team didn’t rest on their laurels. Later that same year, they introduced yet another successor to the AlphaGo family: AlphaGo Zero. This new iteration represented another leap forward in the ongoing journey of artificial intelligence.

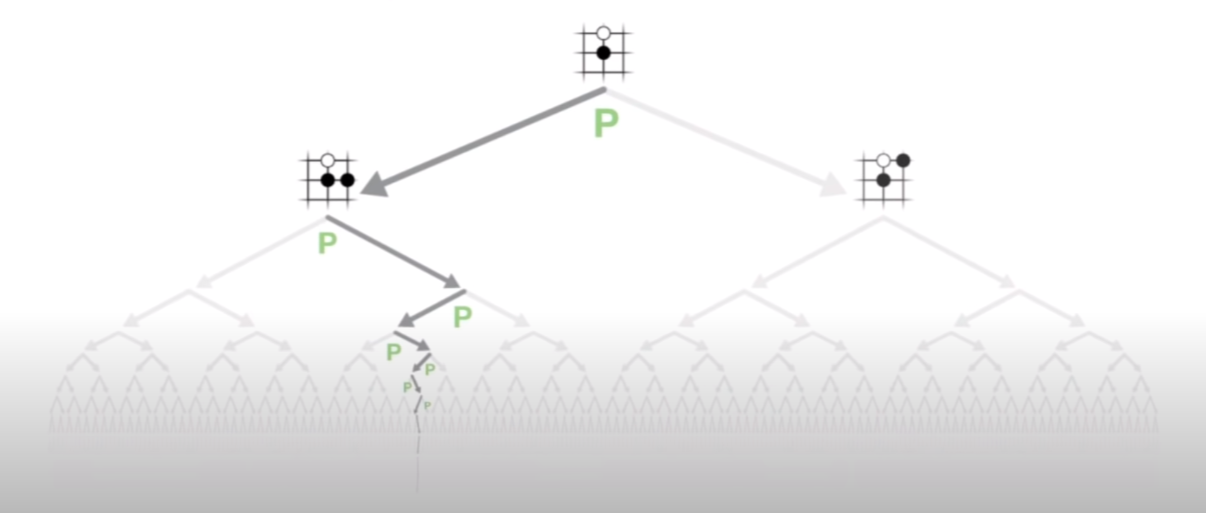

AlphaGo Zero

In October 2017, the DeepMind team announced another breakthrough: AlphaGo Zero. This version of AlphaGo learned to play Go from scratch, without any human knowledge or data, except for the rules of the game. AlphaGo Zero achieved this by using a single neural network, instead of two, that combined both the policy and the value functions. This network was trained solely by self-play RL, starting from random play. Further, AlphaGo Zero used a simpler search algorithm, that did not rely on any randomized rollouts in the evaluation of a postion, but only used the neural network to evaluate the positions. Let us see how exactly this was achieved.

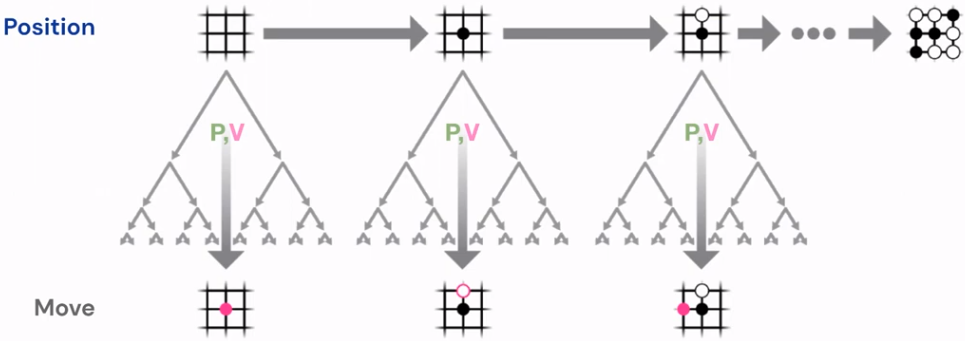

AlphaGo Zero’s Self-Play

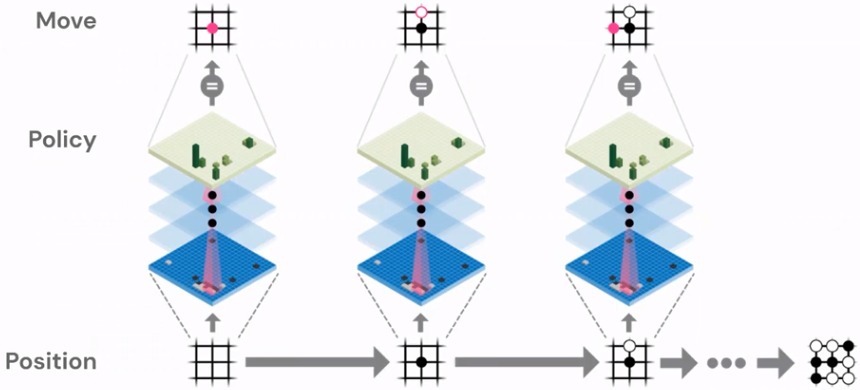

AlphaGo Zero was trained by playing 29 million games against itself, effectively becoming its own teacher. Initially, the network in AlphaGo Zero is initialized with random weights. The system then uses MCTS and the current network to sample moves for both colors, resulting in completed games of Go. These games serve as a basis for updating the network.

The network still outputs a probability distribution over all possible moves for a given board position. However, instead of predicting the moves that human experts would make, the network is now trained to predict the moves that AlphaGo Zero itself made in the self-play games. The probability distribution of moves generated by the network is compared to the actual moves made during the games.

From each position, AlphaGo Zero executed MCTS using its neural network, and then updated the network with the results of the search. We want the raw neural network to predict the action that was chosen by an entire MCTS. One can think of trying to compress what was achieved using look ahead into the new neural networks. The network’s value estimation is updated based on the outcomes of these games.

Consequently, the accuracy of the network can be improved through gameplay. This improved network is then used to play more games. A more accurate network leads to better-guided MCTS, which in turn results in better moves. These high-quality moves can then be used to further improve the network. This cycle of improvement—better networks leading to better moves, which lead to better networks—is repeated continuously. This process reminds of a method called policy iteration, a technique used for finding optimal policies in Markov decision processes. However, instead of using a greedy policy improvement, AlphaGo Zero employs MCTS to select actions that outperform those suggested by the raw network. In this way, AlphaGo Zero utilizes an enhanced lookahead version of the raw network.

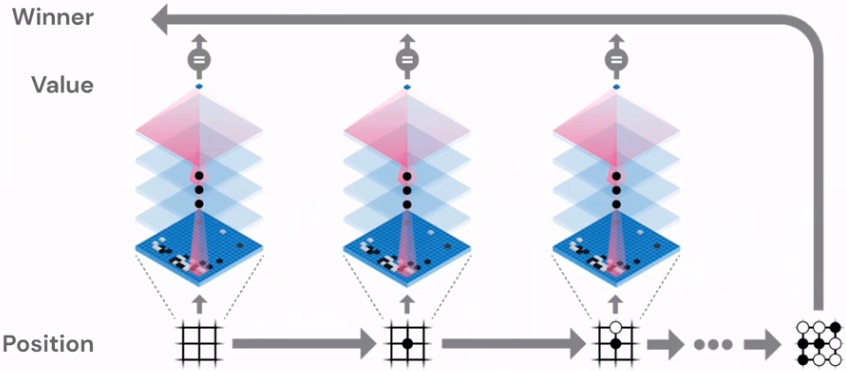

Unifying the Policy and Value Networks

One of the intriguing aspects of merging the policy and value networks into a single entity is observing the transformation of the loss function. This function is a blend of two well-known loss functions: Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Cross-Entropy, augmented with L2-Regularization. The MSE component is crucial for training the value network, while the Cross-Entropy part is essential for training the policy network. Regularization is employed to prevent overfitting, as having more parameters would invariably lead to better training loss, but might not necessarily result in better generalization.

The Performance of AlphaGo Zero

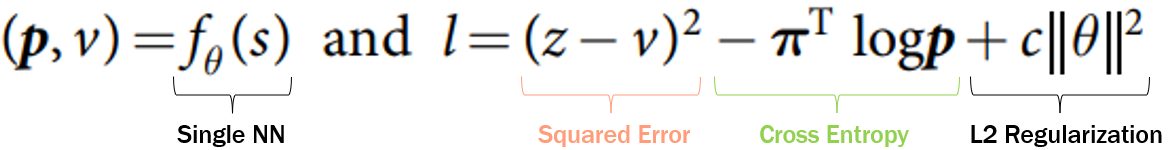

In the figure below we can see the performance of AlphaGo Zero during its training. At its inception, AlphaGo Zero begins by playing random moves. However, after just three days of training, it managed to defeat AlphaGo Lee, the version that triumphed over Lee Sedol, with a score of 100-0. After 27 days, AlphaGo Zero bested AlphaGo Master, the version that defeated Ke Jie, with a score of 89-11. By day 40, AlphaGo Zero had become the world’s best Go player, surpassing all previous versions of AlphaGo.

On the right of the figure, one can see the Elo-rating comparison of all AlphaGo versions in blue, contrasted with the strength of the raw network in gray and previous algorithms in red. It’s noteworthy that choosing moves solely based on the probability distribution outputted by the network is much weaker than the combination of the network with MCTS.

The strength of the algorithms was evaluated by playing games against previous versions of AlphaGo. The algorithms were given five seconds of thinking time per move and 1600 simulations for each MCTS. The results are depicted in the following figure.

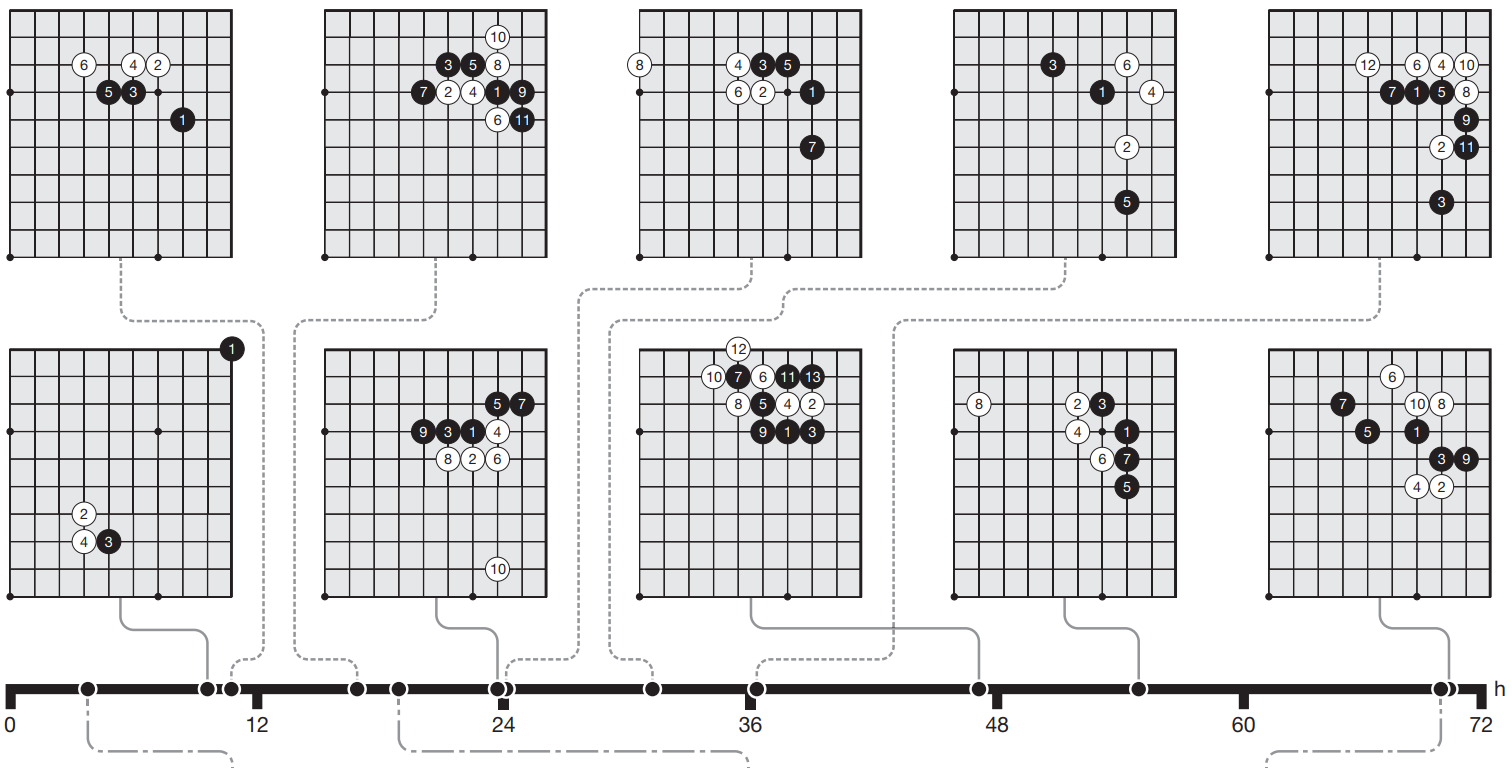

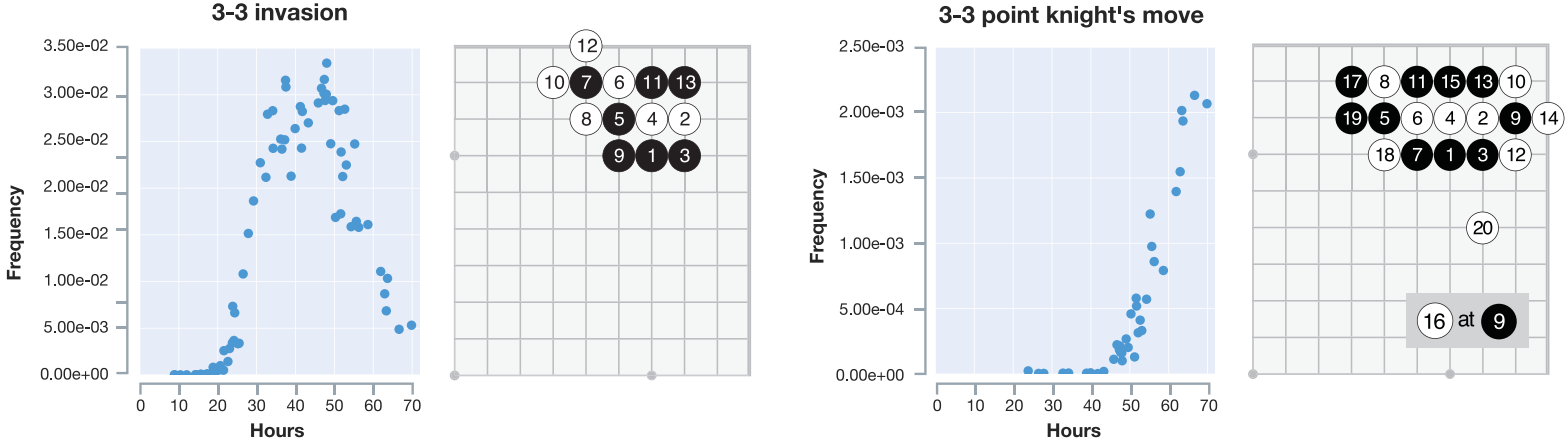

AlphaGo Zero’s Discovery of Opening Patterns

Over time, humans have developed patterns of moves (especially at the beginning of a Go match) that are considered optimal. These patterns are known as josekis. One of the most remarkable aspects of AlphaGo Zero is that it rediscovered human opening patterns that took thousands of years to develop, as well as some novel moves that were discarded or overlooked by humans. The following figure shows a timeline of the training process and when the different josekis were discovered.

Humans can learn from AlphaGo Zero

AlphaGo Zero not only rediscovered known josekis, but also invented new ones. This demonstrates the algorithm’s ability to uncover new strategies and patterns previously unknown to human players. Interestingly, some josekis, considered optimal by humans, were discarded by AlphaGo Zero. This shows that the algorithm can challenge and enhance human knowledge, pushing the boundaries of conventional wisdom. The figure below shows that AlphaGo Zero initially picks up some patterns but discards them after further training if they are deemed inferior. This adaptability is a key factor in its success.

Discussion

Contributions

For the first time in history, AlphaGo and its successor, AlphaGo Zero, demonstrated the superior performance of algorithms over humans in the game of Go. Their victories against world-class human players underscored the potential of artificial intelligence in mastering complex tasks. One of the most remarkable aspects of AlphaGo Zero is its ability to learn from scratch, without any prior human knowledge. Through a process of self-play, it was able to acquire strategies and tactics that even the most skilled human players had not discovered.

Moreover, the techniques used in AlphaGo are not limited to the game of Go. They represent a general approach to artificial intelligence that can be applied to a wide range of problems. In fact, the DeepMind team generalized their approach of AlphaGo Zero to other board games, such as chess and shogi (Japanese chess). They developed a program called AlphaZero, which used the same algorithm and network architecture as AlphaGo Zero, but with different input and output layers to accommodate the different rules and board sizes. AlphaZero was able to learn chess and shogi from scratch, and defeat the world’s best programs in both games, such as Stockfish (the 2016 world chess champion) and Elmo (the 2017 world shogi champion). For more details on AlphaZero, you can refer to the paper “Mastering Chess and Shogi by Self-Play with a General Reinforcement Learning Algorithm” by Silver, David et al. (2017).

Limitations

While the performance of AlphaGo and AlphaGo Zero is impressive, the neural networks they use are complex and difficult to interpret. This lack of explainability makes it challenging to understand the reasoning behind the moves made by the algorithms. This can be particularly challenging for beginners in Go, who might not find value in move suggestions without understanding the follow-up plan.

In addition, AlphaGo Zero required a large amount of data—equivalent to more than a single human’s lifetime experience—to achieve its performance. While this is still more efficient than previous methods, it suggests that there may still be room for improving the data efficiency of AI systems.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed reading this blog post and learned something new! In conclusion, the evolution and triumphs of AlphaGo represent a significant milestone in the field of artificial intelligence. AlphaGo Lee, the first version to defeat a world champion in the intricate game of Go, showcased the power of integrating traditional Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) techniques with modern Deep Learning. This achievement highlighted the potential of merging classical AI methods with contemporary machine learning techniques. However, the journey didn’t end there. AlphaGo Zero, a subsequent iteration, exhibited an even more remarkable capability. Trained entirely from scratch, without the need for pre-existing human game data, it managed to surpass the performance of all other Go-playing algorithms. The impact of AlphaGo and AlphaGo Zero extends beyond the AI community. They have inspired human Go players to learn from their strategies, leading to improvements in their own gameplay and understanding of the game. The story of AlphaGo is a testament to the exciting possibilities that lie at the intersection of artificial intelligence and human curiosity.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Dr. Mathias Niepert and M.Sc. Marimuthu Kalimuthu, for their guidance and support throughout this project.

References

All references were last accessed on 09.02.2024.

Papers

- Silver, David, et al. “Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search.” nature 529.7587 (2016): 484-489.

- Silver, David, et al. “Mastering the game of go without human knowledge.” nature 550.7676 (2017): 354-359.

- Silver, David, et al. “Mastering chess and shogi by self-play with a general reinforcement learning algorithm.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.01815 (2017).)

- He, Kaiming, et al. “Deep residual learning for image recognition.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016.

Blog Posts

- AlphaGo

- AlphaGo Zero: Starting from scratch

- Innovations of AlphaGo

- Was ist ein Convolutional Neural Network?